No matter what style of music you write or play, having knowledge of the elements that make it up is key to becoming the best musician you can be. When it comes to creating chord progressions, there are several tools great writers have at their disposal, such as scales, melody, and harmony.

In jazz, blues, and country music, however, one of the other key elements to gain an understanding of is the turnaround . Without it, a lot of the music we listen to would sound dull and repetitive. But just what is a turnaround in music and how can you use it to make your songs more interesting?

In this guide, we'll learn the many different functions of turnarounds and see how you can implement them in your chord progressions, no matter what style of music you play.

What is a Turnaround Progression?

The best way to explain turnarounds is to start by imagining that you’re telling a musical story, and you’ve reached a point where you need to bring things back around, tie up some loose ends, or set the stage for the next part of your tale.

A turnaround progression is the perfect tool for all of that.

It's essentially a sequence of chords, typically placed near the end of a phrase or section, that takes you back to the beginning of a section (I chord or tonic chord) or prepares you to move forward. They can also be used to resolve a piece of music rather than transition into a new part.

From a theoretical standpoint, turnarounds use harmony as part of a chord progression. For example, in a 12-bar blues progression, the turnaround often happens in the last two bars, setting you up to go right back into the first chord at the beginning of the progression.

One classic example is the I-VI-II-V progression .

In the key of C major, this would be C (I), A minor (VI), D minor (II), and G (V). This sequence leads naturally back to the C chord, creating a sense of closure while also pushing the music forward.

If you've listened to enough blues music in your life, this progression probably feels like second nature to you. Your brain can subconsciously sense where the music is going.

But why are turnarounds so seemingly ingrained in our musical psyche?

To answer that, we have to look back in history.

The History of the Turnaround Progression

Turnarounds are nothing new.

In fact, music historians say they've been a fundamental part of music for centuries. The familiar sound of the V chord resolving to the I could be heard in the music of the 1500s, especially throughout Western Europe.

If we push forward a few hundred years to the advent of blues and jazz, however, this is where turnarounds truly started to find their form.

Blues music started taking shape in the American South during the 1920s, and turnarounds became a key component of the genre’s 12-bar structure.

The turnaround was a necessary tool to bring the music back to the start of the chord progression, especially with the repetitive and cyclical nature. The earliest turnarounds were basic, to say the least, typically involving a V-I cadence that signaled the end of one cycle and the beginning of another.

However, as jazz music developed in the 1930s, musicians began to experiment with more complex and sophisticated turnarounds. Musicians like Duke Ellington and Charlie Parker pushed the boundaries of what we knew was possible with chord progressions, using extended chords, substitutions, and chromaticism in their turnarounds.

Nowadays, we can hear turnarounds in all kinds of music, from country to pop and folk to rock and roll. Though these turnarounds are harmonically different, they all share the same basic function.

The Function of a Turnaround

Regardless of genre, a turnaround should act as a musical punctuation mark, signaling the end of one section and preparing the listener for the beginning of another.

However, beyond reinforcing the structure of an otherwise repetitive genre like blues, turnarounds can also create transitions between different sections of a song.

For example, you can use one to bridge a verse and a chorus for a smoother transition between sections.

In "Sweet Home Alabama," we have a D-C-G chord progression. To move back into the verse or the chorus, the G chord acts as the turnaround.

On the other hand, turnarounds can also be used to introduce a sense of anticipation. You might choose to hold on a IV chord for a little bit before ultimately going back to the I. The time you spent suspended on that Iv creates anticipation for the listener, as they have an idea of where you're going, but you just haven't quite made it yet.

If you really want to get creative, you can use a turnaround to surprise your listener. For example, if you're writing a pop song with a V chord that leads back to the I, you might substitute it at one point with a flat VI chord. In the key of C major, this would be an Ab instead of a G.

I personally love these little unexpected twists in music, especially considering how many songs recycle the exact same chord progressions.

Types of Turnarounds

If you want to start incorporating turnaround progressions in your music, there are infinite ways to do so. I often find that it's best to start with the basics.

In most pop music, you'll find common chord progressions that use the same turnarounds. If you're writing a song that you want to integrate with a familiar sound, I recommend trying these out:

- I - V - IV - V: This turnaround progression is one of the most straightforward around. You've no doubt heard it in many popular songs.

- I - VI - II - V: Another great turnaround for pop and jazz music.

- I - VI - IV - V: If you want more of a cyclical feel in your song, this turnaround progression is a solid choice.

As a guitarist, I learned about the turnaround progression long ago by playing 12-bar blues. In most blues songs, the turnaround is found in the last two bars.

For example, if we were in the key of C major, in Bars 1-8, we might have the progression:

C-C-C-C-F-F-C-C

In bars 9-10, we'd go from the dominant to the sub-dominant:

G-F

Finally, we'd get to the turnaround in bars 11-12:

C-G

The very last G in the turnaround progression is what we'd use to create that sense of anticipation before going back to the C, or I chord at the top of the 12-bar progression.

A More Advanced Approach

If you feel like you can write a 12-bar turnaround progression with your hands tied behind your back, you might want to explore more advanced turnarounds. Jazz is a great place to start, as many jazz tracks use substitutions and extensions to create richer harmonic turnarounds.

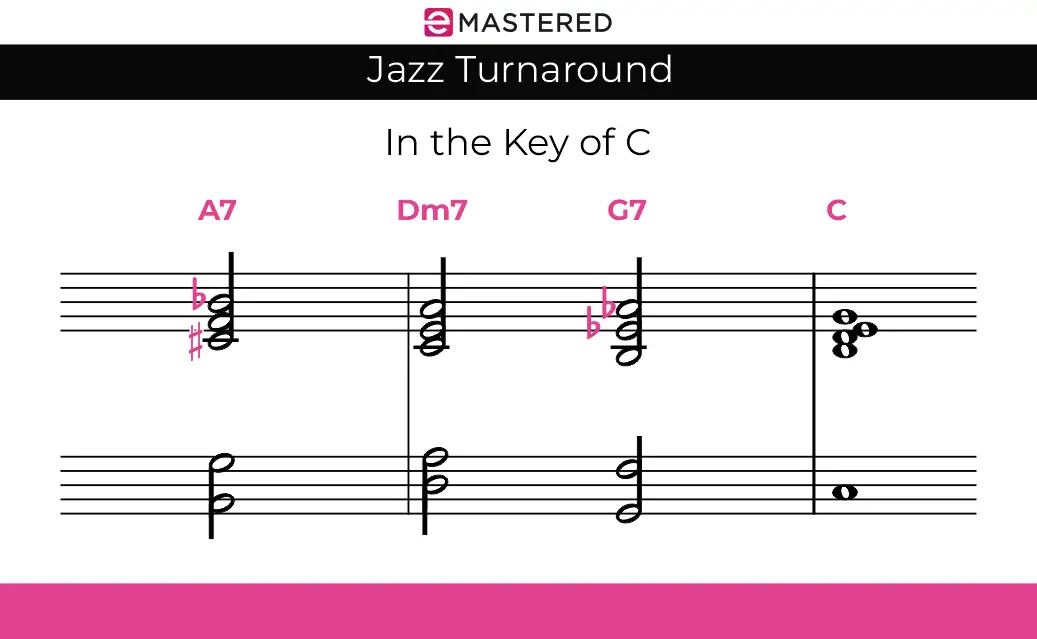

Let's say you're writing in the key of C major still. Your basic turnaround progression would look like this:

Cmaj7 - Am7 - Dm7 - G7

We could then spice it up by substituting A7 for Am7, which would make it:

Cmaj7 - A7 - Dm7 - G7

Taking it one step further, we could use extensions on that chord progression to get even more color:

Cmaj7 - A7#5 - Dm9 - G13

While the progression above might seem complicated, the reality is that it's just built on the same basic turnaround progression that we started with.

A Few Turnarounds In Popular Music

There are literally thousands of popular songs I could think of that have great examples of turnarounds, but I figured I'd just provide you with a few examples to give you a better idea of how they work in the real world.

"Sweet Home Chicago" by Robert Johnson

"Sweet Home Chicago" is a classic example of a 12-bar blues turnaround.

In this blues standard, as with many, the turnaround happens in the last two bars of each 12-bar cycle.

This particular track has a basic I-IV-V-I progression in the key of E, which looks like this:

E - A - B7 - E

In the last part of the progression, the track moves down from E to B7 in a chromatic fashion (D-C#-C-B) before going back to E at the top.

"Autumn Leaves" by Joseph Kosma

"Autumn Leaves" is arguably one of the most iconic jazz standards of all time.

The song uses a basic ii-V-I progression, though many players will improvise with jazz extensions.

If we were to look at the turnaround from the original key of G minor, it's basically Am7 - D7 - Gm (Am7b5-D7-Gm6)

The use of minor ii chords and dominant V chords gives it that rich harmonic texture before taking us back to the tonic chord.

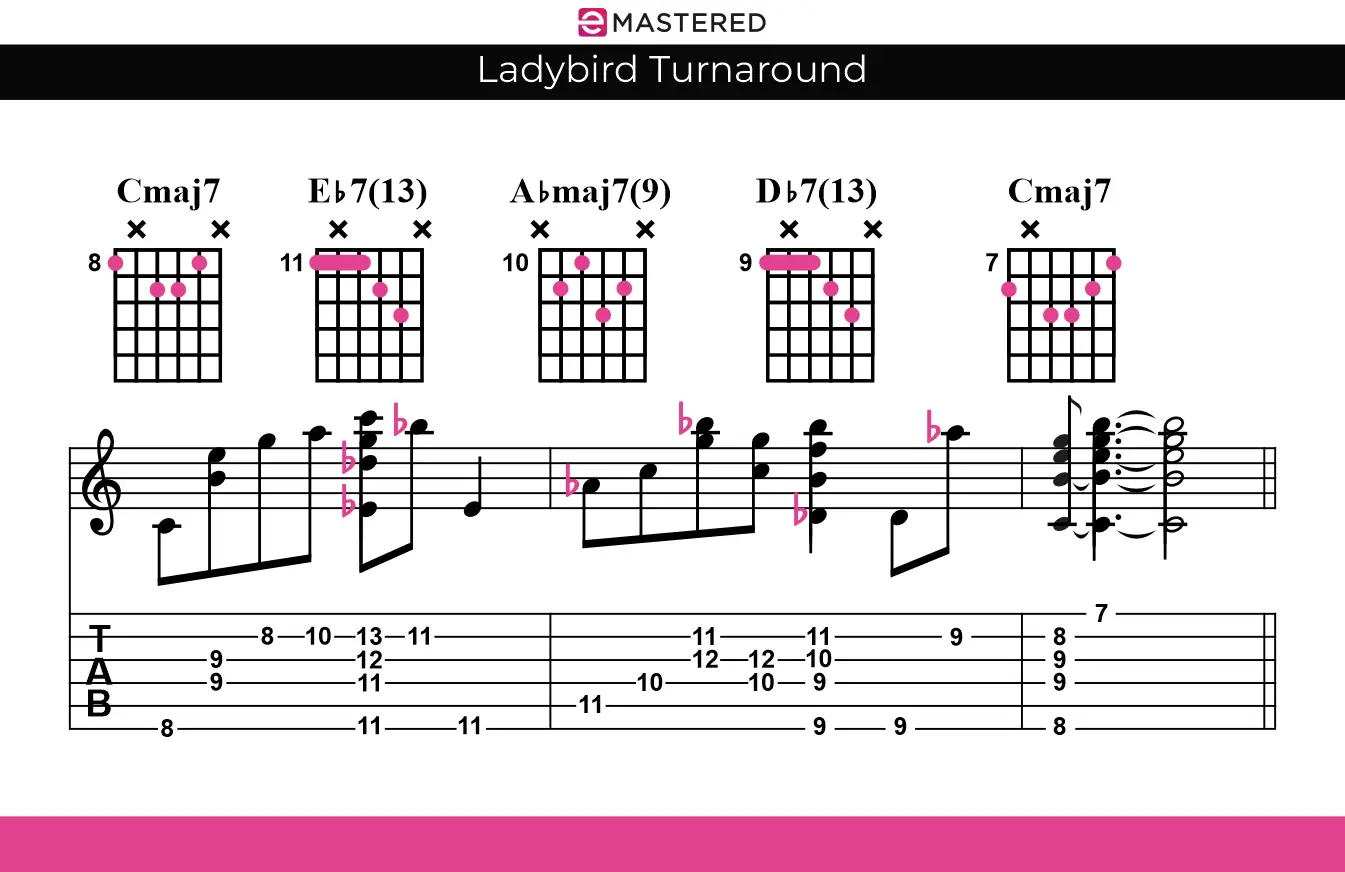

"Lady Bird" - Todd Dameron

One of my favorite turnaround progressions comes from a cool little jazz standard called "Lady Bird."

Using this style of turnaround in your music is a great way to start incorporating minor subdominants or get that "Coltrane" sound.

Typically, the chord progression would look something like this: I7-IVm7-bVII7-Imaj7

In the key of C major, that would look like this:

- C7 (V7 of IV) – The C dominant 7th chord acts as a V7 chord leading into Fm7.

- Fm7 (iv7 ) – The subdominant minor provides a smooth voice leading with its minor quality.

- B♭7 (V7 of V7) – The B♭ dominant 7th chord acts as a secondary dominant, creating a chromatic descending line to the tonic.

- Cmaj7 (Imaj7) – Finally, we resolve to the tonic major 7th chord, providing a sense of resolution.

You can take this idea even further like in the progression above, where multiple secondary dominant chords are used.

Final Thoughts

There are so many incredible things you can do with simple chord progressions when you start exploring nuanced elements like turnarounds. I urge you to start exploring songs with turnaround progressions and see how you can use them in your own songs. It's an excellent way to build your arsenal of chord options, especially if you play blues or jazz.