If you've ever sat with musician friends and heard them ramble on about the chromatic scale, or chromaticism, and felt utterly confused you are not alone.

Luckily, the chromatic scale is not a difficult one to master, and this article will furnish you with enough knowledge bombs to to make you feel confident talking about chromatic scales, and using them in your music.

Ready? As Julie Andrews wisely suggested, let's start at the very beginning...

Music Theory Basics

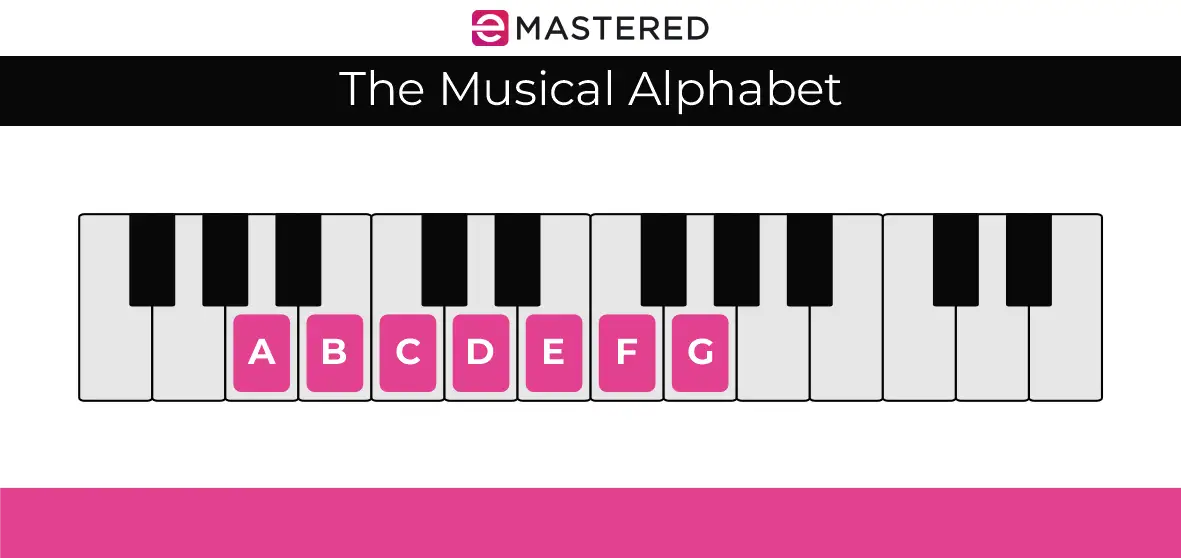

The Musical Alphabet:

If music theory is completely new to you, it's important to know how musical note names work in order to understand the chromatic scale.

The musical alphabet runs from A-G, and repeats as notes get higher. On a piano, all the white notes are named this way:

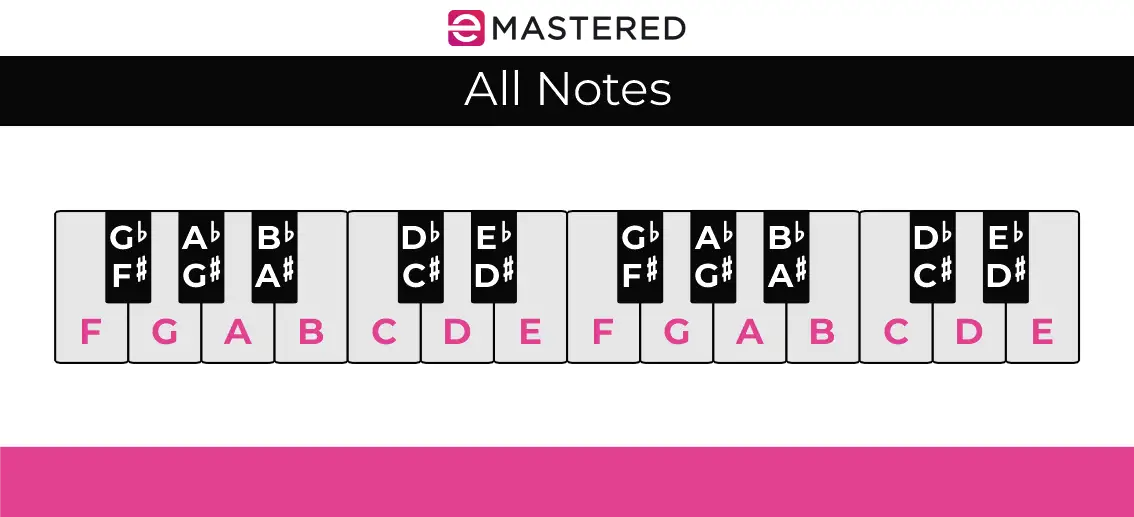

The black keys (great band, btw) in between the white keys take their names from the neighboring notes. So, the black key between F-G can be referred to as F# (F sharp), or Gb (G flat), even though they're the same notes. With western tuning, they're enharmonic equivalents of the same note.

Here's all the notes on a keyboard:

What Is A Scale?

A scale is a series of notes played in a sequential order. In Western music the two most common types of scale are the major and minor scales - known as diatonic scales. A diatonic scale has seven pitches.

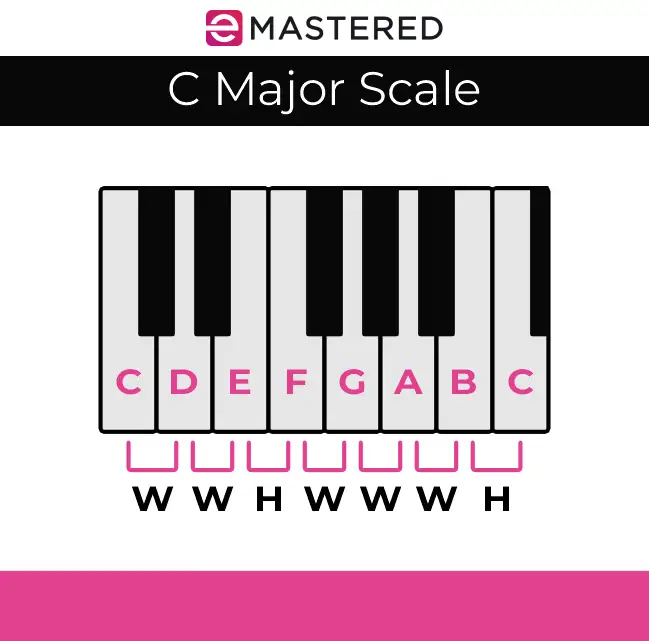

There's a whole heap of other scales, but the easiest scale to play, and visualize, is the C major scale.

On a piano/keyboard, you simply play every white key starting on middle C, until you reach the next C above it.

See the W's and H's on the image above? They mark the whole steps (W) (or tones) and half steps (H) (or semitones) that make up a major scale.

What Are Whole Steps and Half Steps?

A half step is the smallest interval between two notes in western music, and on a piano. In the above example you'll see E-F and B-C are marked as half-steps (H), because there are no keys in between them.

A whole step is comprised of two half steps. In the example above, F-G is a whole step, because of the black note in between them (remember our friend F#/Gb?).

Every scale, whether it's a major or minor scale, or one of the many modes that exist, is made up of a distinct and unique pattern of whole and half steps. As I mentioned there's lots of them. But there is only one chromatic scale.

What Is The Chromatic Scale?

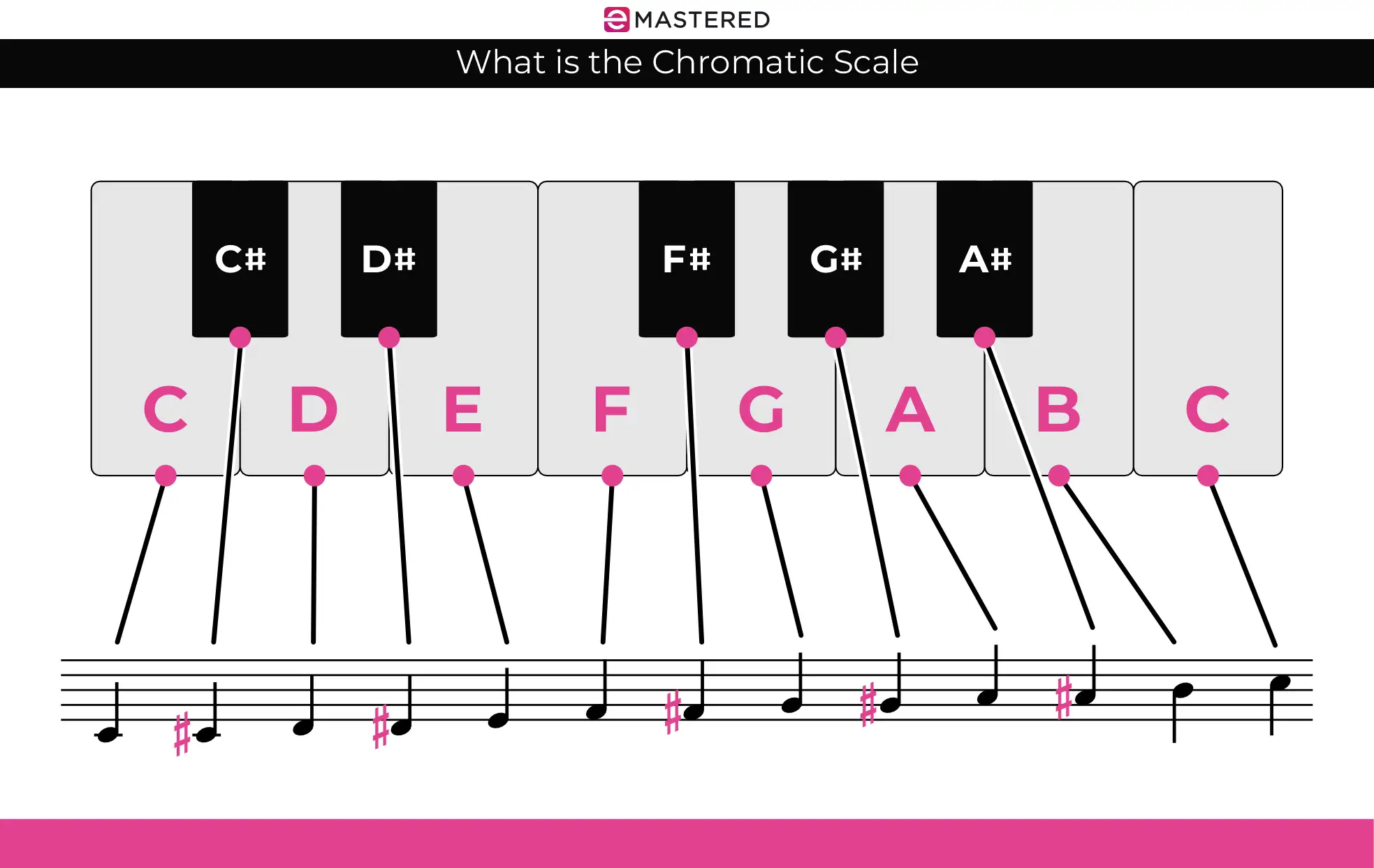

Put simply, the chromatic scale is a scale that only uses half step intervals in ascending or descending order. Another way of putting it is that the chromatic scale uses all twelve tones sequentially.

On a piano you play all the white and black keys between your first note and your last one. On a guitar, it's every note from an open string to the 12th fret.

Starting on C, the chromatic scale would look like this:

And it sounds like this:

The chromatic scale is a unique scale in that it doesn't have a tonal center. Unlike other scales you can start it wherever you like and it will always sound the same.

The example above isn't a C chromatic scale. It's THE chromatic scale, starting on C.

How Many Notes Does The Chromatic Scale Have?

Because it doesn't follow an interval pattern like major or minor scales, the chromatic scale played over one octave will have 13 notes.

That's the 12 notes available in Western tuning, plus the last note - the starting note an octave higher.

But it's rare to use the chromatic scale in its entirety, except when practicing. We'll look at some examples of music that use the chromatic scale, and how to use it in your own music later.

First, let's look at how to play the chromatic scale.

How To Play The Chromatic Scale On A Piano

You could just use one finger to plunk up (or down) all the notes, but this won't help with your chops.

Instead, follow these rules of thumb (pun intended):

- any time you play a black key, use your third finger

- any time you play a white key in your right hand use your first finger (thumb), except if it's preceded by another white key, in which case use your second finger

- any time you play a white key in your left hand use your first finger (thumb), except if it's followed by another white key, in which case use your second finger.

So if you were playing ascending chromatic notes starting on C the right hand fingering would be:

1 3 1 3 1 2 3 1 3 1 3 1 2

The same pattern for left hand fingering would be:

1 3 1 3 2 1 3 1 3 1 3 2 1

It'll feel clunky at first, so start slowly. Very slowly. Let your fingers learn their own way around the keyboard and in time you'll be galavanting up and down the chromatic scale like The Flash.

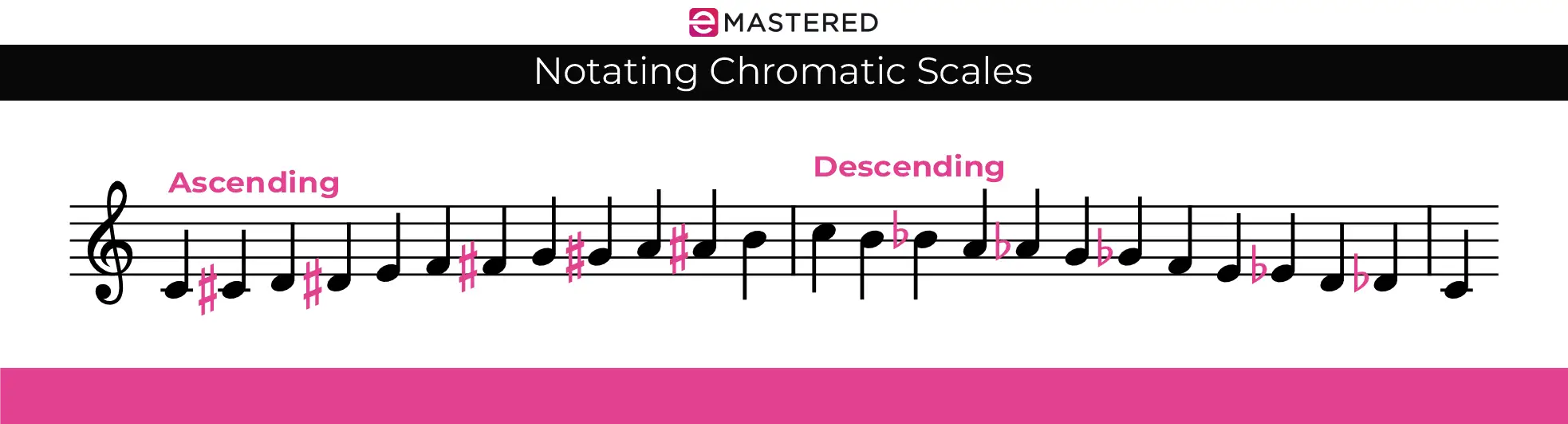

Notating Chromatic Scales

This section is for music theory buffs, but it's worth knowing how the chromatic scale is notated to give you a broader understanding of the whole concept.

As I touched on earlier, the general guideline is that an ascending chromatic scale is written with sharps, and the descending chromatic scale with flats.

Here's an example of both, starting on C:

Another rule is to have at least one note on every line of the stave. This makes it easier for the musician to read.

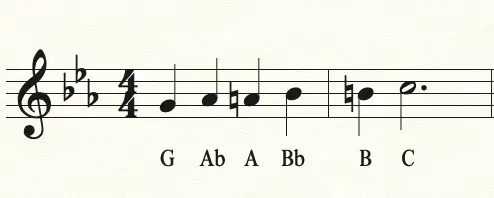

In reality, a composer will notate the chromatic notes in a way that makes sense to the key signature. In the key of Eb, which has 3 flats, a chromatic passage running from G to C would be notated: G - Ab - A - Bb - B - C

Variations Of Chromatic Scales

Yes, there's only one chromatic scale, but there's a bunch of different ways of playing it.

The Ascending Chromatic Scale

Starting on any note (let's stick with C for now), play all the white and black notes going up the keyboard until you reach the next C.

C-C#-D-D#-E-F-F#-G-G#-A-A#-B-C

The Descending Chromatic Scale

In this variation of the chromatic scale you'll be going down the keyboard from your starting note. Again, starting on C:

C-B-Bb-A-Ab-G-Gb-F-E-Eb-D-Db-C

The Parallel Motion Chromatic Scale

In this variation two hands (or players) will start on different notes, but head in the same direction.

For instance, your left hand starts on a C, and your right hand starts on a D#, and both rise up an octave in half steps. This one sounds a little cartoony and fun:

The Contrary Motion Chromatic Scale

In a contrary motion scale both hands will start on the same note and move in opposite directions. This results in a kind of Shephard Tone-esque rising/falling effect:

The Contrary & Parallel Motion Chromatic Scale

In this variation the player switches up between contrary and parallel motion in both hands.

Sequential Chromatic Scale

We're getting even more granular here! In this variation you play only part of the chromatic scale, before starting the sequence again a half step up.

The example below plays four ascending notes of the chromatic scale starting on a C, before beginning again on C# and repeating the sequence.

Other Variations

In jazz music it's not uncommon to add even more variations to the chromatic scale by adding in different intervals on specific notes.

Examples of the Chromatic Scale in Classical and Popular Music

The following chromatic scale examples are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to chromaticism in tonal music.

Rimsky-Korsakov - Flight of the Bumblebee

One of the most famous uses of chromaticism in western classical music.

Chopin - Etude Op 25 No.6

Chopin's music is extremely expressive, in part thanks to his smarts when it comes to chromaticism.

Bruno Mars - Uptown Funk

That section leading into the chorus? That's an ascending chromatic scale.

Metallica - Master Of Puppets

Because where would metal be without chromaticism?

Using the Chromatic Scale in Your Music

The word chromatic originates from the Greek word for color - 'chroma'. Chromatic notes can be used to add spice and variety to your music, provided you don't overdo it.

When adding chromaticism to your own music, or to your gigging chops, try using part of the chromatic scale to get between two notes of the main melody.

Here's two versions of Twinkle Twinkle Little Star. The main melody plays first, followed by the chromatically altered one. It's perhaps not a great example in terms of street cred, but you'll get the idea!

As you experiment with the use of chromatic scales in your playing and music you'll find out which chromatic notes work best with which chord changes.

As an example, let's say you're playing a piece in the key of G where the melody plays B-A-A-C-D , over a chord progression of D7 (the V7 chord) to G (the I chord).

Here's what that sounds like on it's own:

To add a little tension to the melody you could use a chromatic note to get from the C to the D, so now you'd be playing B-A-A-C-C#-D over the same chord progression.

Here's what this new version sounds like:

Unless you're purposely going for an unhinged, crazy effect, the old adage 'less is more ' holds true when it comes to adding chromaticism to your music.

Benefits of Learning The Chromatic Scale

No one will ever pay you write or play a piece of music that is entirely built on purely chromatic scales, even if it's atonal music.

But there's good reasons to learn the chromatic scale:

- it can improve your technique

- it helps develop improvisation skills

- it leads to a better understanding of music theory

- it helps you create more interesting and expressive music

Conclusion

And here ends today's lesson on all things chromatic. Learn how to play it, and use it to spice up your tunes.

Now go forth, and maketh the (chromatic) music!