Let’s face it, writing songs is fun. It’s a great way to express yourself and knowing you’ve written an entire song is hugely gratifying.

But it’s easy to get caught up with the same old same old when it comes to chord progressions (I’m looking at you, Nickelback).

So what do you do when you’re bored with the same four-chord trick you’ve used for the past ten songs? Or when you can’t find the right musical way to support the lyrics?

The answer, my friend, is to go to the library of parallel modes and borrow a chord.

Ready to learn how to add some pzazz to your songwriting? Let's go...

What Is A Borrowed Chord?

Keeping it short and sweet, a borrowed chord is one that creates a harmonic color outside of the primary key by - you guessed it - borrowing from contrasting scale forms.

What?

I know, right? It's almost like a politician wrote that answer.

Depending on where you are with your music theory this may make some, or no sense to you. So let’s break things down a bit further.

Diatonic Chords

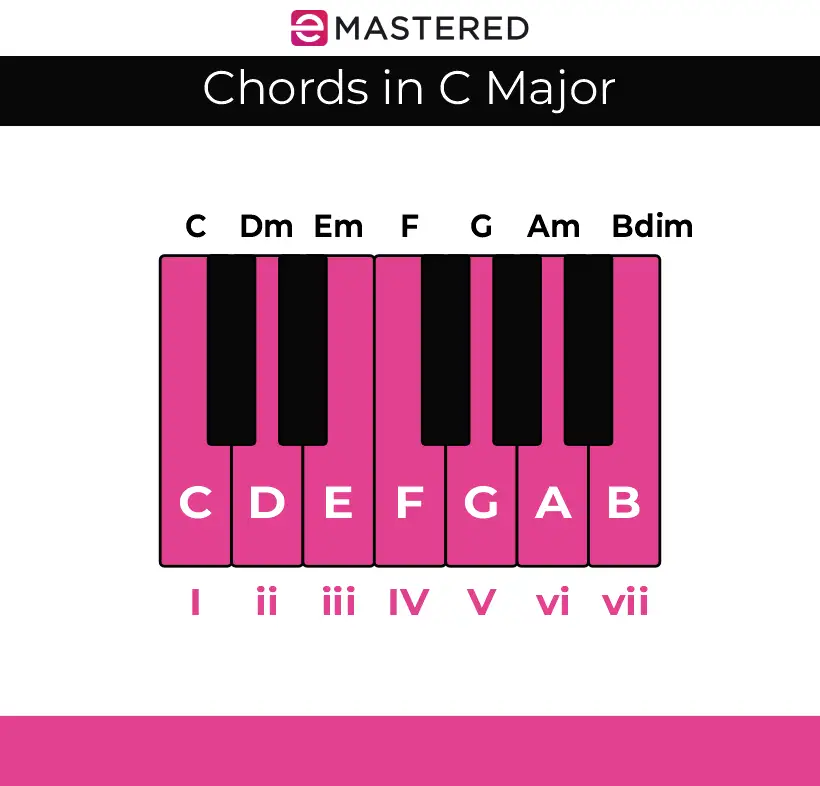

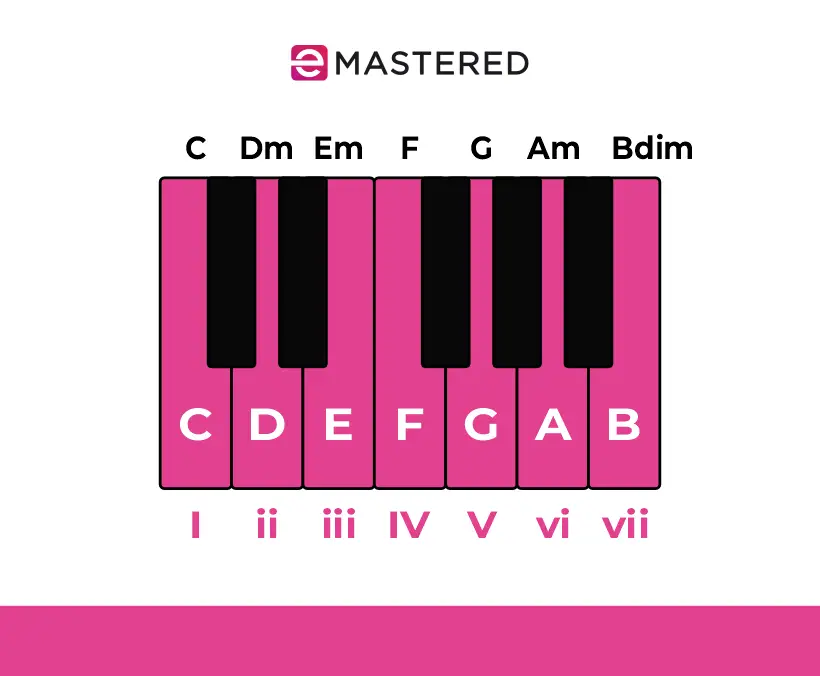

In any given (diatonic) key, there are seven chords based on the seven degrees of that scale. These are what's known as diatonic chords , because they don't introduce any chromaticism or 'outside notes'.

If, for example, you’re in the key of C major you’ll have the following chords based on each note of the scale:

The roman numerals along the bottom refer to the degrees of the scale (from 1 to 7), but are also used to indicate the chord, and whether it's major (uppercase) or minor (lower case).

This is quite fancily known as Roman Numeral Analysis, but don't get sweaty palms about this. It's the same numbering system as the Nashville system - naming the chord after the scale degree the root of the chord is based on.

Anyhoo, I digress.

Diatonic chords only use notes from the scale degrees of the key the music is in. So in the example above, everything will be pretty vanilla. No sauce, no spice.

As you can imagine things can get bland real fast, especially if you're working in a major key. That's why folks turn to borrowed chords.

Borrowed Chords, Once More

So, borrowed chords can also be thought of as color chords - something to add harmonic variety to the music.

As mentioned above, a borrowed chord is one based on a contrasting scale form to the key you're currently in.

But not just any scale. You can't grab a random chord, stick it in your song, and call it borrowed (although, technically I guess it is).

No, borrowed chords can only be derived from parallel keys or modes .

So, next question, what exactly is a parallel key?

Parallel Keys

A parallel key shares the same root note (or tonic note) as the parent, but has a different set of intervals.

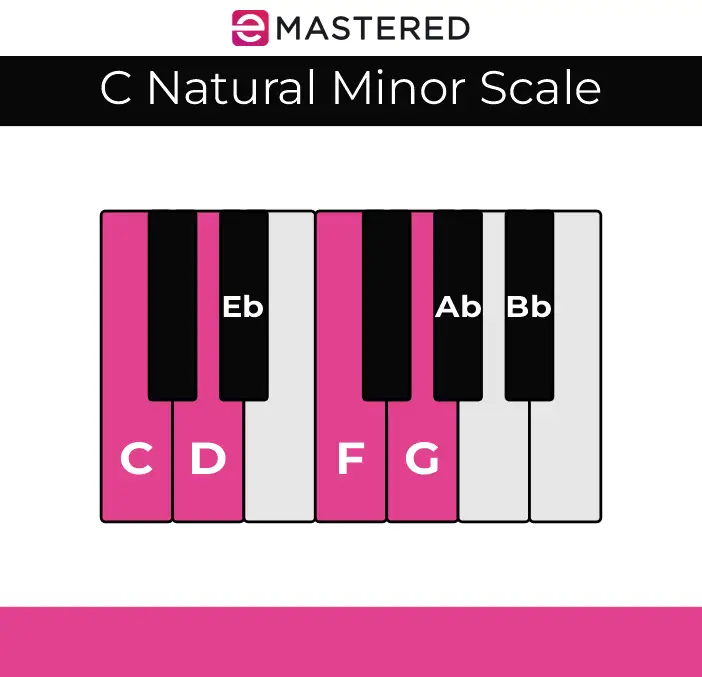

C minor is the parallel minor key to C major. It starts on the same root (C), but has a different set of intervals to make up the scale.

Likewise for the C harmonic minor key (where the Bb is raised a half step to B natural). C natural minor, and C harmonic minor are both a parallel key to C major. All major scales have parallel minor keys.

Parallel Modes

Most common borrowed chords are based on a parallel key. But sometimes it's good to cast your net further and look into modes as a source of inspiration.

Modes can be scary to think about, but in practical terms they're just another set of intervals based on a root, just like a major or minor scale.

So when we're talking about parallel modes in the context of borrowed chords, we mean any mode that begins on the same root note as the home key.

If you're writing a song in a major key and you want to dig deeper than a plain old minor key, you can borrow a chord from a mode instead. As long as said mode starts on the same root note as your original key.

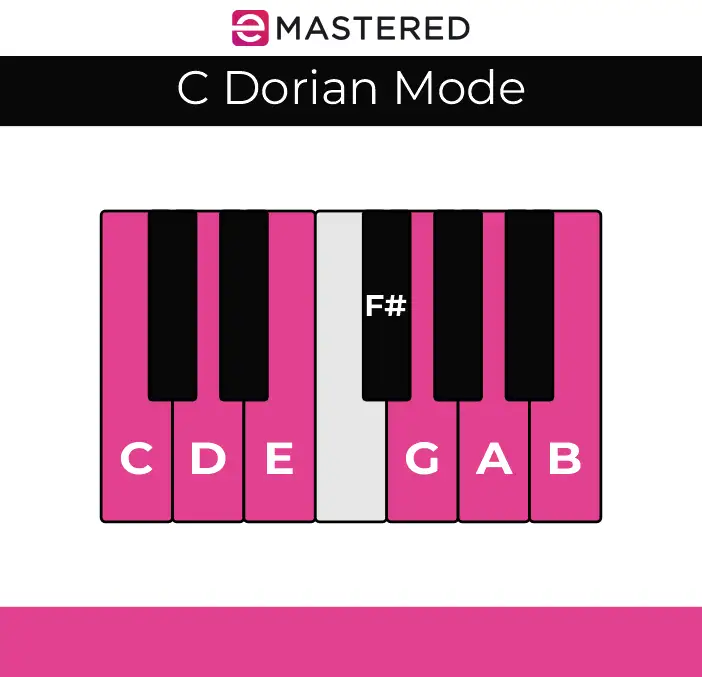

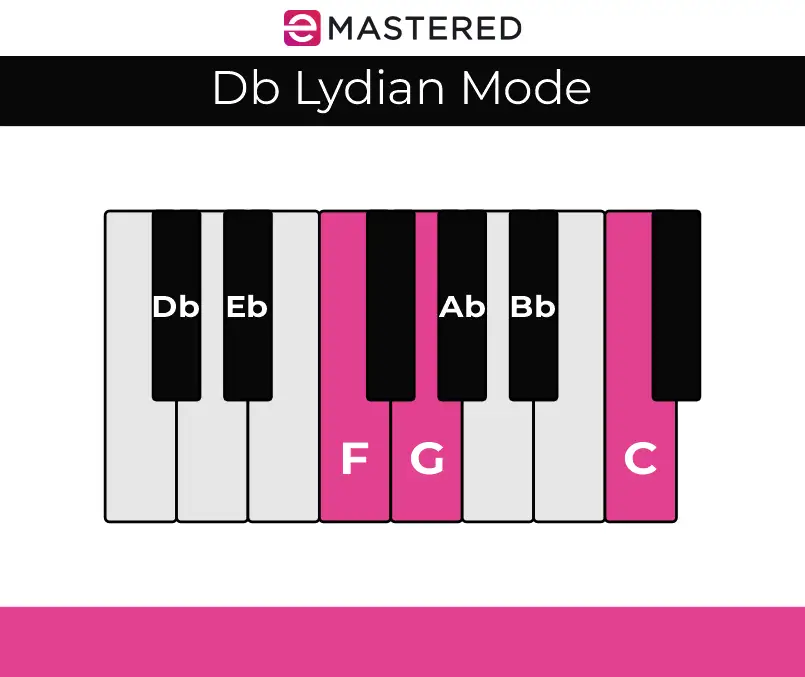

In our C major example, we might look at C Lydian mode to nick a chord from. We'll be looking at an example of this a bit later.

But how do you go about putting all this parallelism into the act of borrowing chords?

Borrowed Chords In Action

Parallel Minor

Sticking with C major for this first example, let's say we've come up with a nice little chord progression based on the first, fourth, sixth, and fifth degrees of the C major scale.

The progression would be:

C - Am - F - G

or

I - vi - IV - V

This is all very diatonic and predictable. To spice things up a bit, we decide to use some non-diatonic chords.

Let's look at the parallel minor scale for inspiration. In natural minor scales the third, sixth, seventh degrees are flattened.

In the C natural minor key, the notes E, A, and B are all flattened. So this time, even though we're using the same scale degrees as the root of each chord, we have some options.

- Am (vi) becomes Ab (VI)

- F (IV) becomes F minor (iv)

- G (V) becomes G minor (v)

Why can't the C chord (I) become C minor (i)? Well, it can, but since it's the first chord in the progression it's also the one that very clearly states that we're in a major key. If you changed it to a minor chord you'd also be signaling to the listener that we're in the key of C minor.

I like the flat six - Ab (VI) - so I'm going to switch that out for the second chord. Now our progression becomes this:

C - Ab - F - G

or

I - VI - IV - V

Fruity indeed.

Parallel Major

Now let's switch to C minor for our key of choice. And I'm feeling lazy so let's just use three chords:

Cm - Ab - Fm

or

i - VI - iv

This time we're using the parallel major key to borrow chords from. To save you scrolling up, here's the C major scale again:

Since we don't want to change the first chord (and thus the home key) there's two options available to us:

- Ab (VI) becomes Am (vi), or

- Fm (iv) becomes F (IV)

The first option sounds distinctly cinematic so let's use the second one and change the minor iv chord to a major chord. Our new progression is:

Cm - Ab - F

or

i - VI - IV

This creates an entirely new (slightly 007) sound for our progression. Thanks Major IV!

Real-World Examples Of Songs With Borrowed Chords

Using a borrowed chord or two in songwriting is super-common. Otherwise music would sound pretty crappy. Here's some classic songs that make use of a chord that's borrowed from a parallel scale.

Radiohead - Creep

This popular ditty from the 90s makes heavy use of our old friend, minor iv, borrowing from the G minor mode. As the song is in simple 'A' form the borrowed chord pops up in every stanza.

The first time is around 0:36 on the word cry . The song, which is in G major, switches from a IV chord (C), to a C minor chord (iv).

It's a beautiful moment, and switching between a major and minor mode is great way of driving home a fierce emotion.

David Bowie - Space Oddity

Firmly grounded in the key of C major this song uses the same major-minor mixture with a borrowed minor iv.

In the chorus, Bowie switches to the F minor on the word papers , at around 1:38.

I'd also suggest that there's another borrowed chord just before it on the word Tom . This could get me in fisticuffs with music theory purists, but hey ho...

The chord in question is based on the third degree of the scale, and in major keys that equates to a minor chord. But this is E major (III), so Bowie is borrowing, slightly, from the whole tone scale here.

Since the whole tone scale can't create traditional triads, I would say instead he's replacing the G in the E minor (iii) chord with the G# from the whole tone series on C, to make it E (III).

The golden takeaway here is, don't let rules hamper your creativity. If it sounds good to you, go ahead and play it.

Louis Armstrong - What A Wonderful World

This old-timey classic makes use of a flattened sixth, a chord from the parallel minor key.

We're in F this time, and when we get to the phrase and I think to myself at around 0:20, the (normally) D minor (vi) chord is replaced with Db (VI).

Phil Collins - Against All Odds

Apologies for using Sir Phil as an example, but it's a cracker, chock full of borrowed chords.

The particular chord I want to highlight comes in the chorus, and is based on the supertonic , the second degree of the scale.

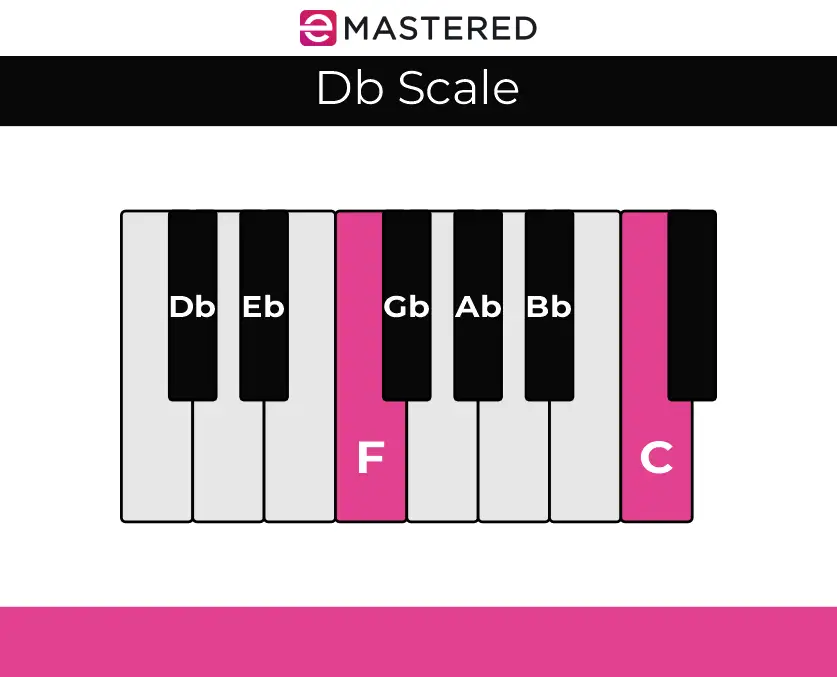

We're in Db here, so here's the Db major scale:

The second degree is Eb, and the ii chord would normally be Eb minor (Eb - Gb - Bb). But by borrowing from the Lydian mode in Db our man Phil raises the Gb, making the Eb chord a major one.

It happens on the word empty at around 1:08.

Phil Collins. Love him or hate him, there's bunches of modal interchange happening in this song, and it's a good exercise to go through the song and figure out where all the 'out of place' chords are coming from.

Borrowed 7th Chords

When you add seventh chords, or other extended chords into the equation you can conjure up even more flavors. Just make sure that whatever extended note you're adding also borrows from the parallel scale you're using.

Keys, Scales and Modes: A Footnote

Confusingly, the terms keys, modes, and scales are all kind of interchangeable when we're discussing borrowing chords.

A scale is a broad term for describing a set of ordered pitches. A key is a kind of shorthand for a specific scale. A mode however, is a specific type of scale derived from another scale, but starting on a different key.

One thing that borrowed chords don't do is modulate, or change the key. Only borrow something for a short moment, much like if you borrowed your mate's guitar. Then get things back to home base.

Don't stress about the the ins and outs of it all, but know that borrowed chords can also be referred to as mode mixture, or modal interchange.

The term borrowed chords sounds way cooler though, just as they do in music.

Armed with all this info, go forth and maketh the music!