Harmony is one of the three essential building blocks in music. It provides light and shade, tension and release, and can take the listener on a moving journey.

If you’ve studied harmony and how chords function, you’ll probably know how to create powerful emotional landscapes using certain chords at just the right place.

But what happens if you flip that harmony upside-down & inside-out?

Enter the dazzling world of negative harmony.

The term 'negative harmony' has been around since the 1980s, but has recently enjoyed a surge in popularity thanks to Jacob Collier’s enthusiastic discussions of the principle.

In this article, we’re going to leap headfirst into the world of negative harmony, exploring the theory behind it, where it came from, and how it can take your own music to new levels.

Ready? Set phasers to stun...

What is Harmony Anyway?

In order to understand negative harmony better, let's take a quick look at what good ol' regular harmony is.

Building Blocks: Intervals and Chords

In music, harmony is built on intervals - the distance between two notes.

When someone (like Nickelback, for instance) stacks two or more notes together, they create chords. These are not just random stacks; chords are built using a predetermined series of intervals to give them a unique sound and texture.

Harmonic Landscapes: Chord Progressions

Stick a sequence of chords together and you get a chord progression. The combination of the harmony created by the individual chords, and that created by the chord progression itself, is what gives a piece of music it's emotional weight.

The Importance of Harmony

Think of a piece of music as a human body (bear with me here): rhythm is the pulse and movement, melody forms the skeleton, and harmony is the flesh, giving it depth and character.

Harmony is critical in music as it provides context to a melody. Even if that melody is performed acapella, there is an implied harmony behind it.

Harmony has a strong influence on the mood of the music; changing it can alter the vibe completely.

What is Negative Harmony?

Negative harmony is the concept that every 'traditional' chord can be flipped around a central axis to create a negative counterpart.

These negative chords have the same harmonic function as their positive buddies, but take on an entirely different emotional quality, often making the music darker or more introspective.

The same theory applies to melodies; every tune in the positive world has a negative mirror image.

Another way to think about negative harmony is as a kind of plugin that reimagines musical ideas. Major chords become minor chords, and melodies take unexpected and interesting turns.

It's a great tool to have in your arsenal for happy composing, but understanding negative harmony requires some theoretical gymnastics.

Having some simple music theory concepts under your belt will help with understanding this blog post; chords , basic harmony , and how Western scales function are some good topics to be familiar with, to avoid getting royally confused.

Now we've got that chestnut out of the way...

The Theory Behind Negative Harmony

The core idea of negative harmony is that every chord has a polar opposite - a 'negative' version.

To get these negative counterparts, chords are flipped around a central axis, which is directly between the root note and the fifth.

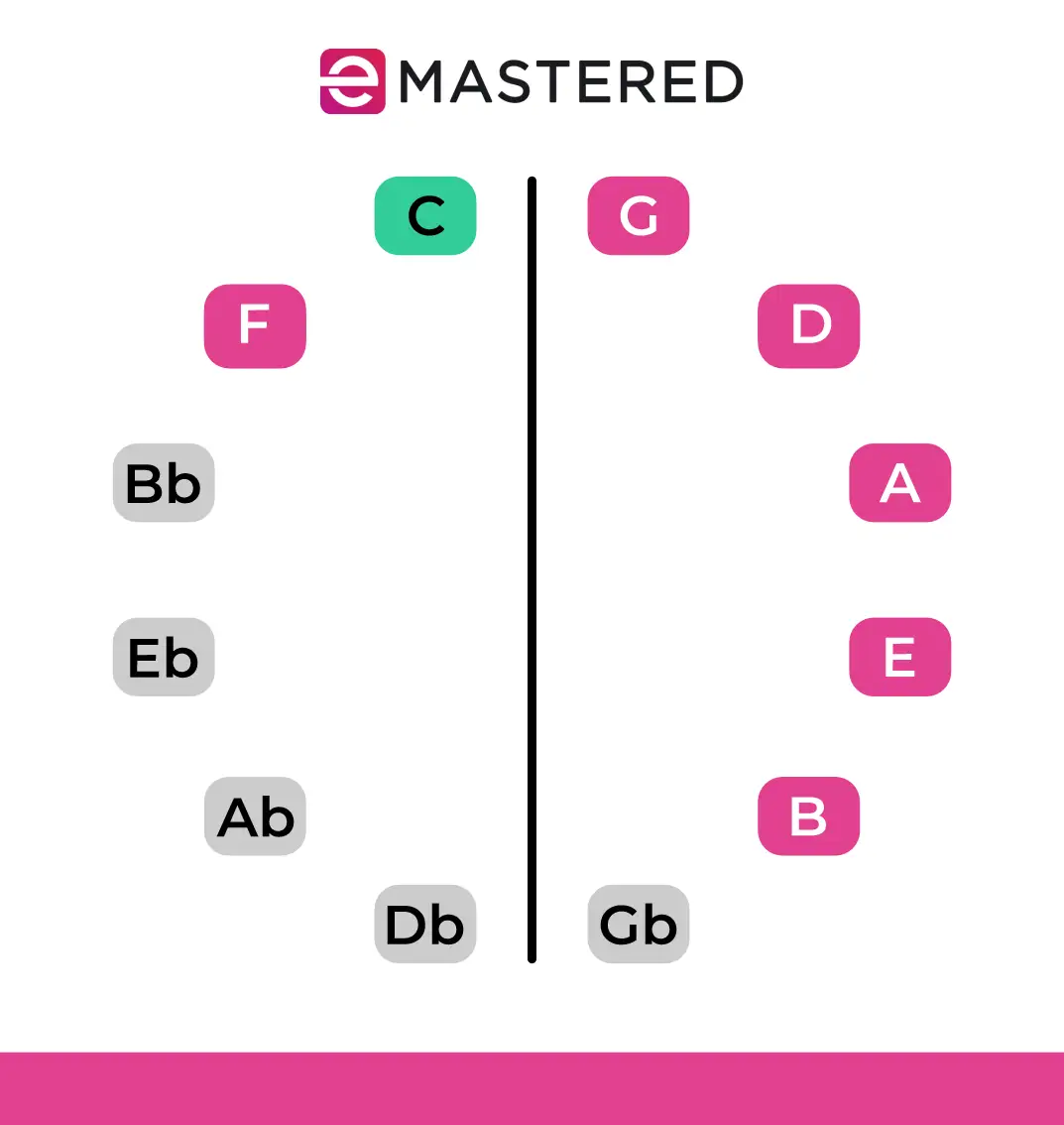

To work out negative harmonies, first find the key center. Then, use the Circle of Fifths to establish the polarities for that key by drawing a line across the circle using the root note as a reference.

For example, in the key of C the axis-flipping happens between the root note C, and the fifth, G.

In the image above, I've drawn a line between C and G, which gives us everything we need to figure out the notes in a negative chord in the key of C.

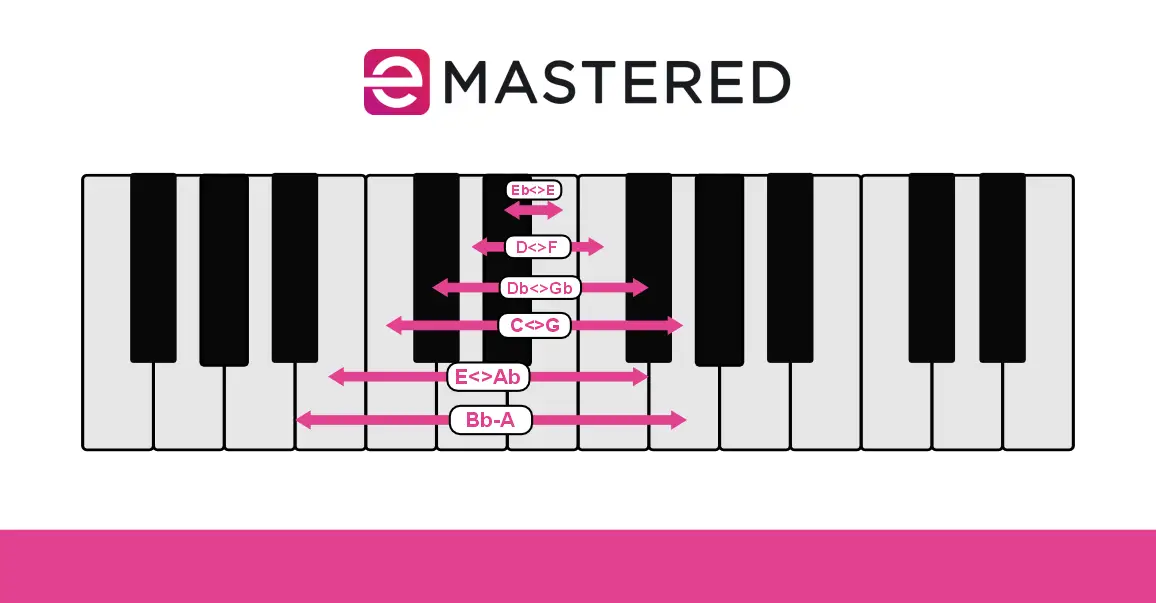

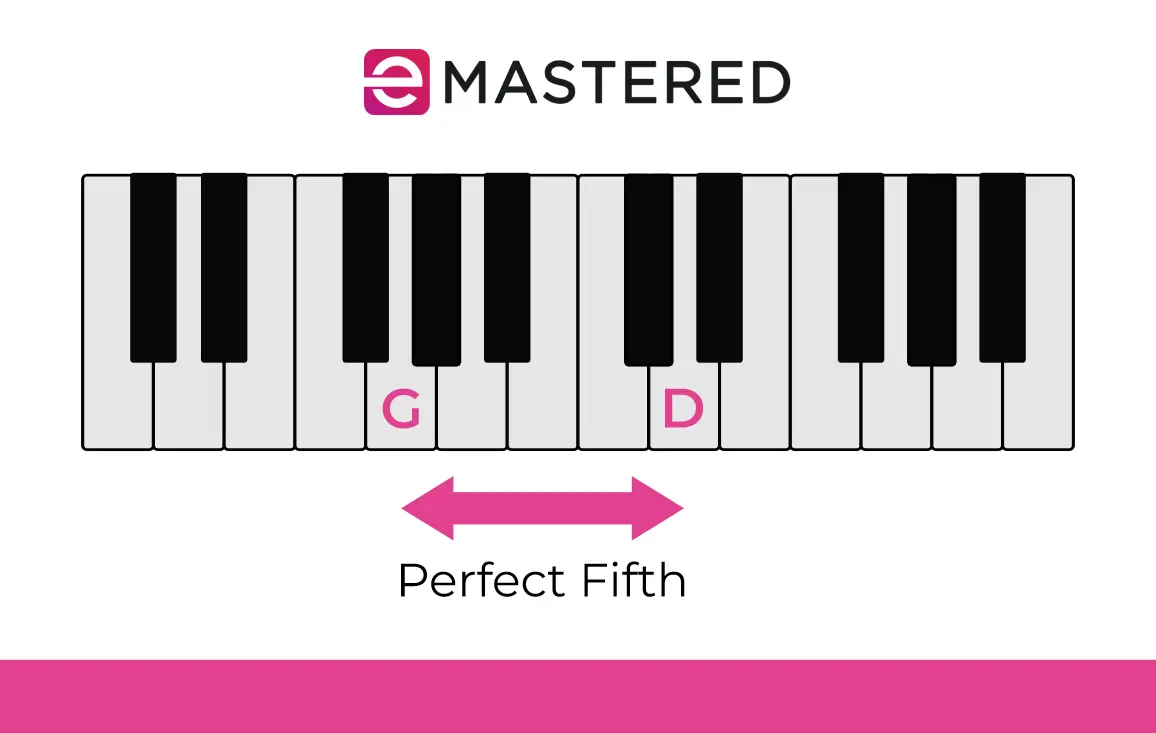

If you're a piano player you might find it easier to visualize in keyboard form:

As I mentioned above, the axis is between the root and the fifth, so in the key of C, the axis point is between E and Eb.

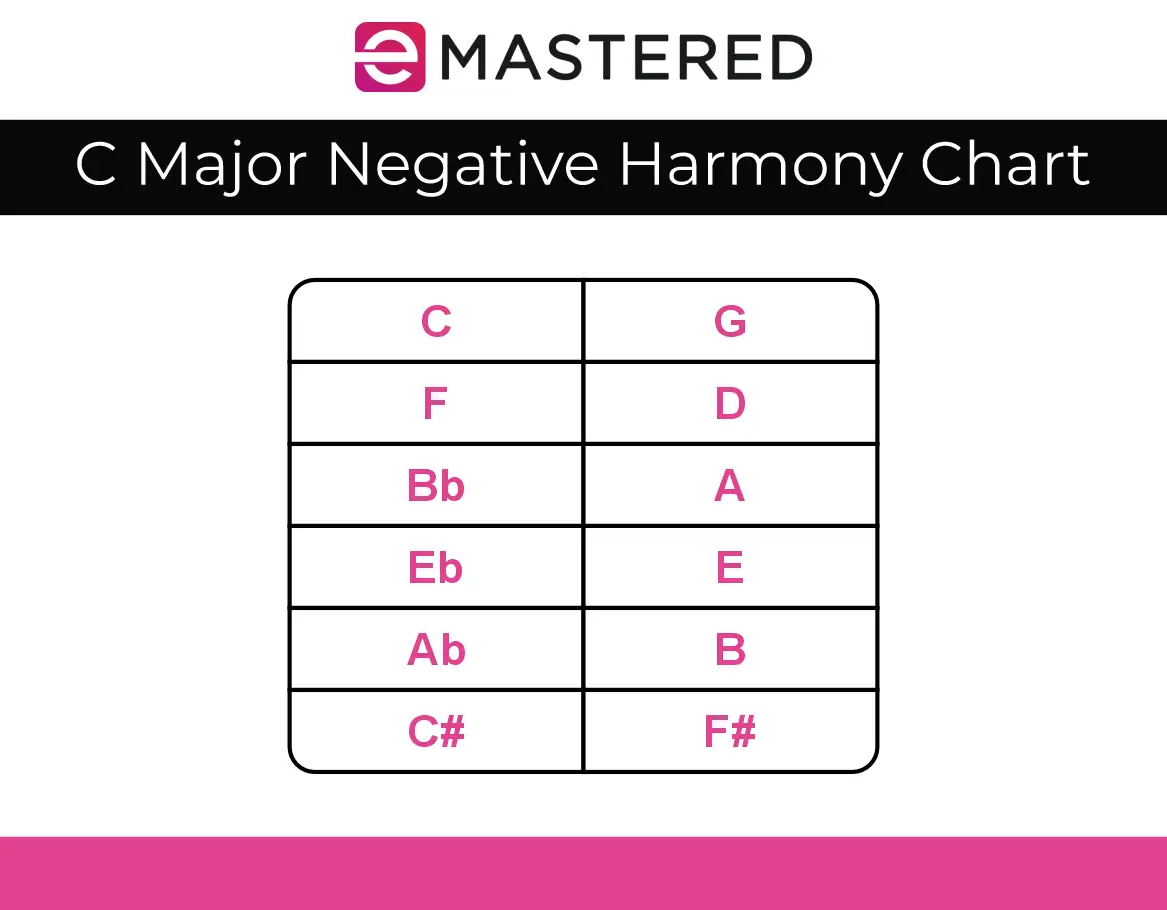

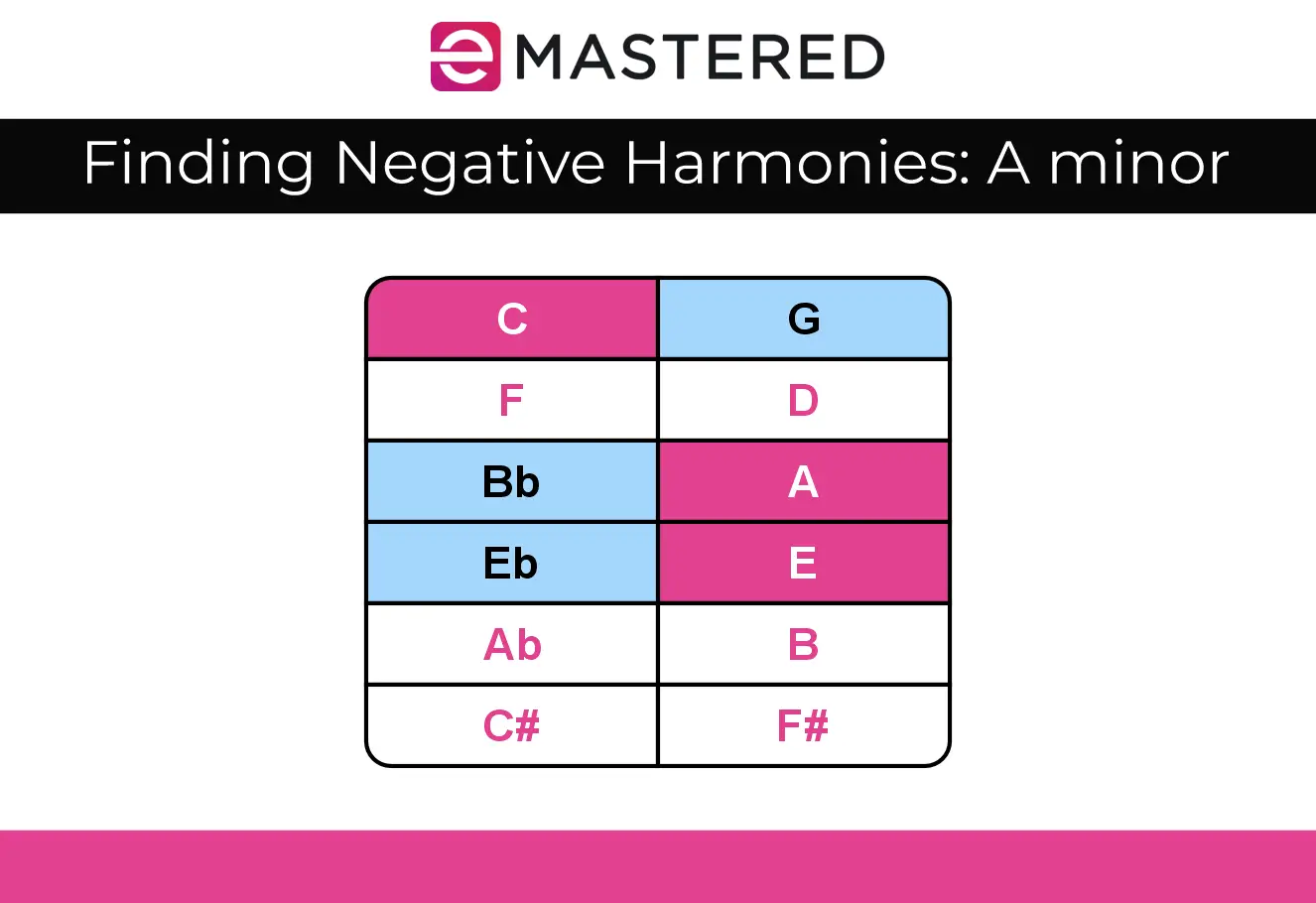

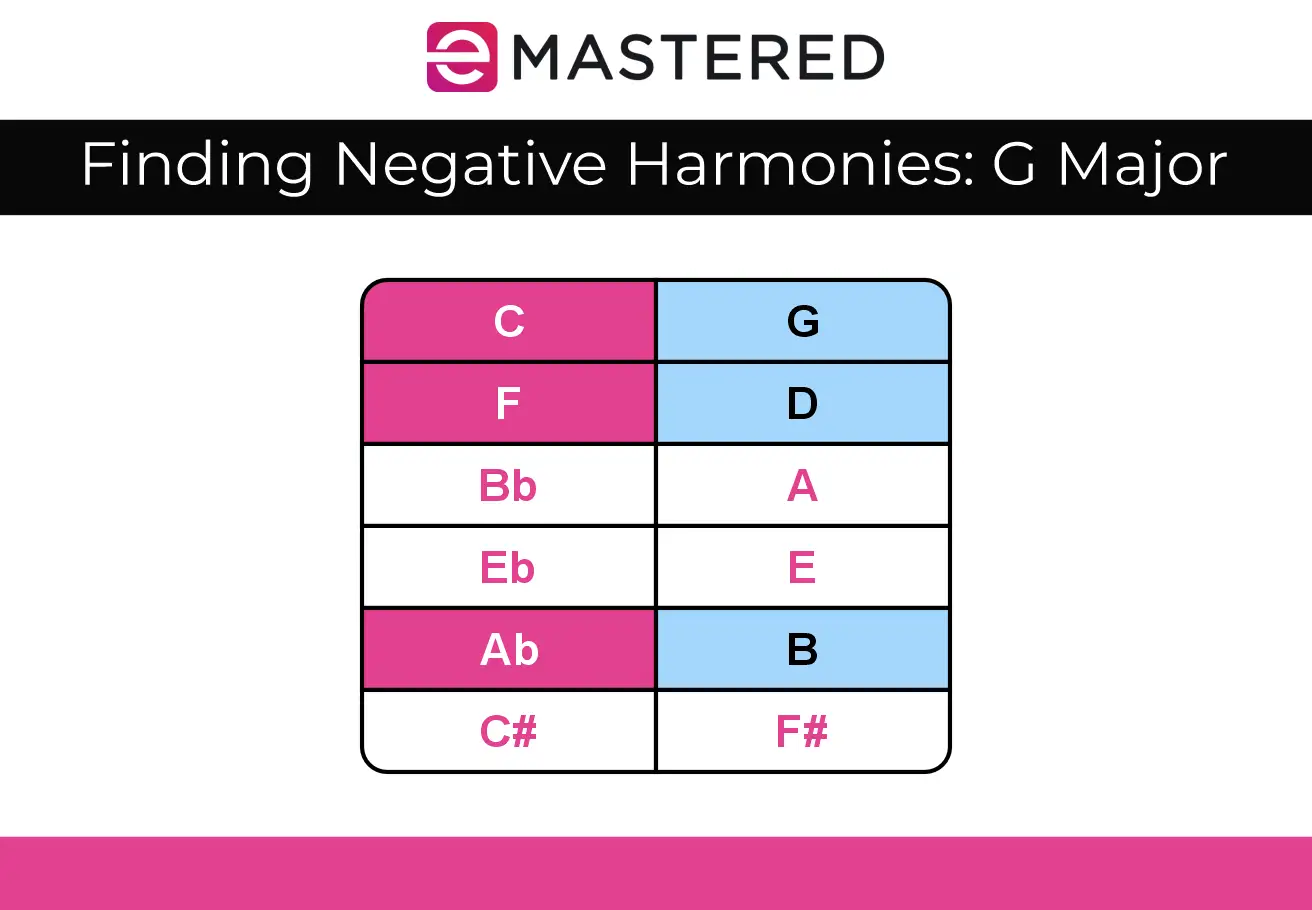

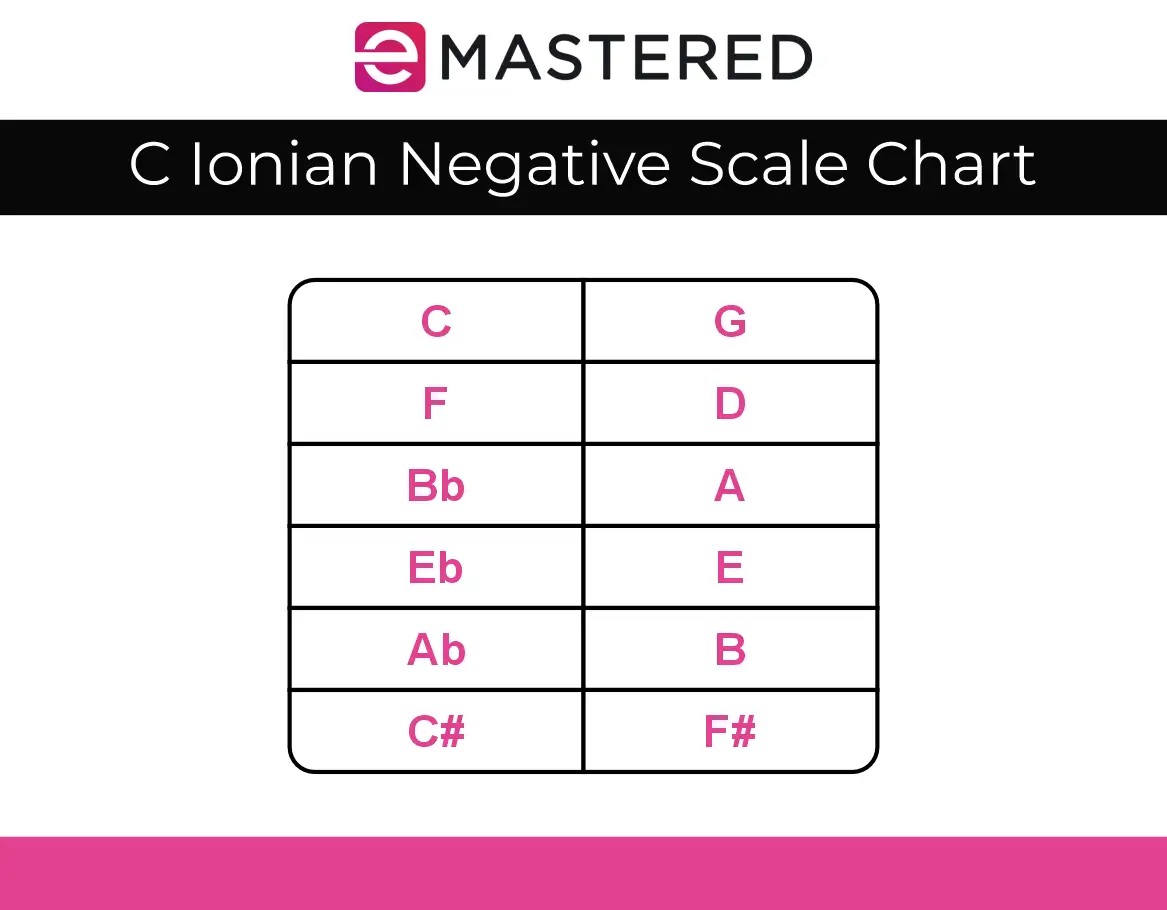

To make things easier on the eyes, here are all the polarities in a chart form:

Talking about the technique is all well and good, but it will make more sense seeing the process in action.

Let's take a look at some chords in C major and work out their negative counterparts.

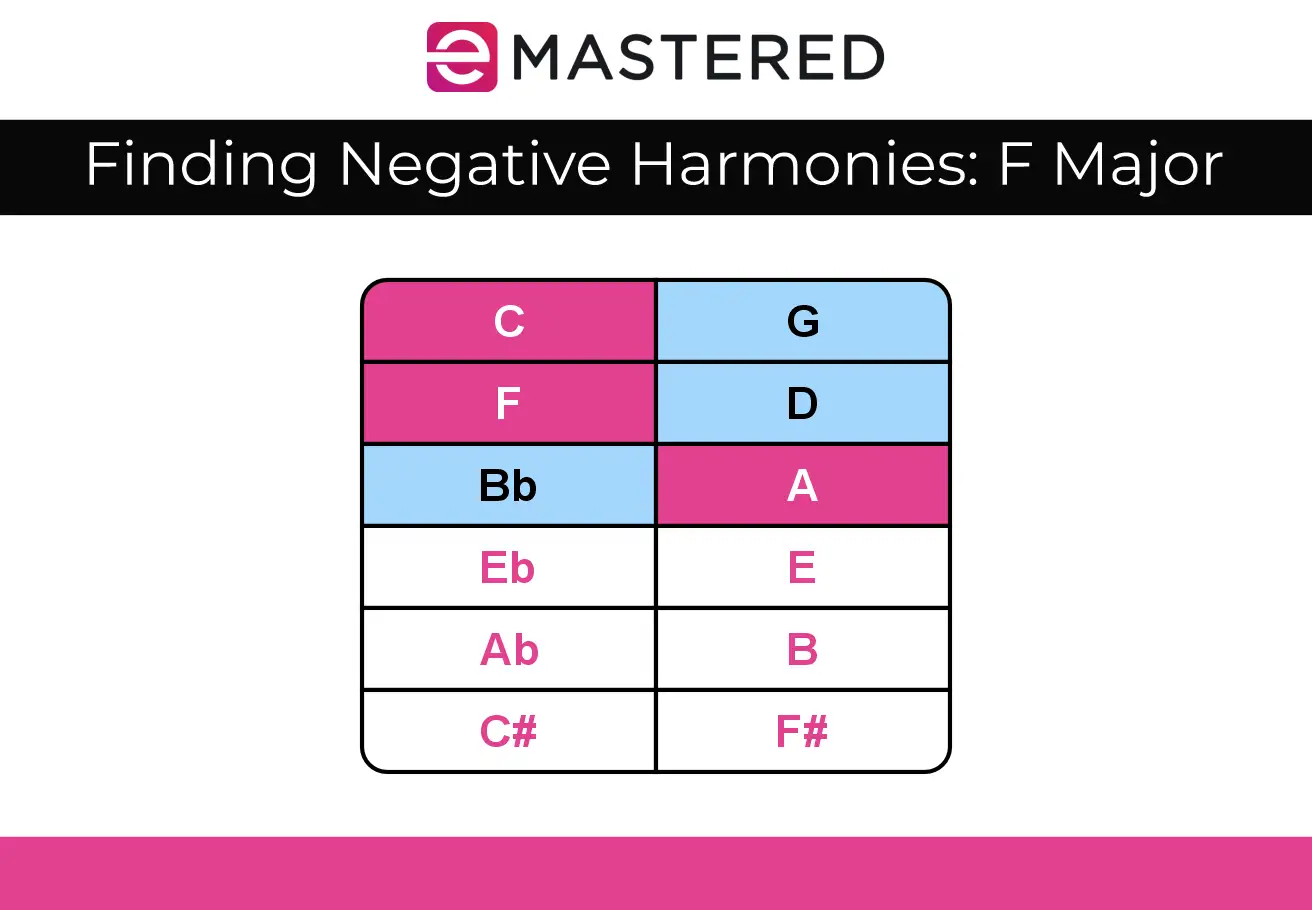

An F major chord is made up of the notes F-A-C . The negative counterparts to these notes are D-Bb-G . In root position, this becomes a G-minor triad.

An A minor chord is spelled A-C-E . The negative version will be spelled Bb-G-Eb , or an Eb major triad.

A G major chord ( G-B-D ) becomes an F minor chord in negative harmony ( C-Ab-F , inverted to root position: F-Ab-C ).

Finding the Root Note of a Negative Chord

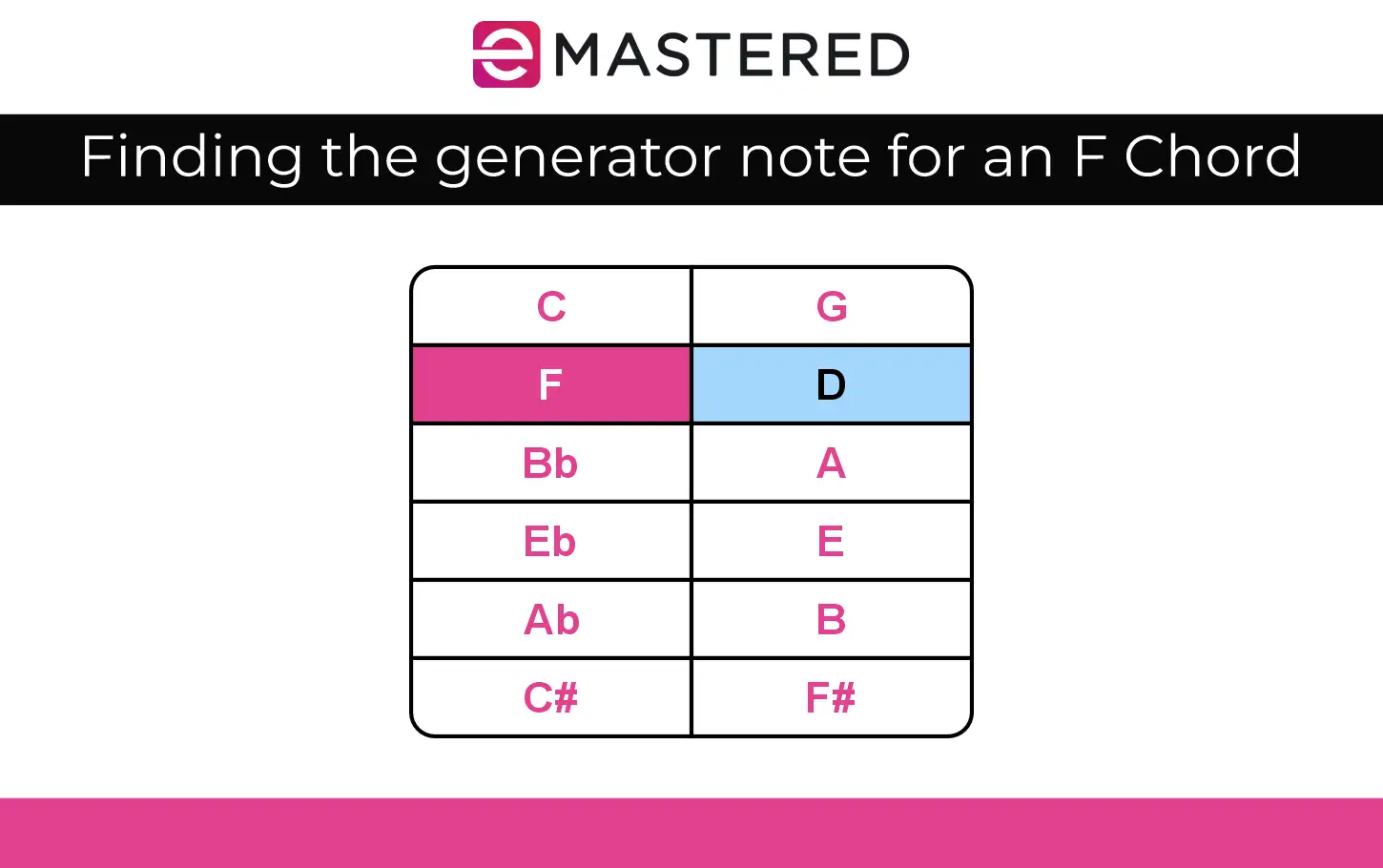

How do we know what the root note of a negative chord is? First you need the generator note.

The generator note is the negative counterpart to the root note of the original chord. In the first example (F major) the root note is F. The generator note is therefore D.

The root of a negative harmony is always a perfect fifth (or 7 half-steps) below the generator note. In this example, the root note of our negative harmony chord is G.

How to Quickly Work out Negative Harmony

Going through the circle of fifths in this way to figure out negative chords can be time consuming, so here's a shortcut to working out the negative harmony of chord progressions.

- Find the root notes of all the chords in your progression

- Invert them on the axis

- Transpose those new notes down a perfect 5th

- Invert the chord type (major becomes minor, and vice versa)

Here's a mind-blowingly simple chord progression. We're still in C major:

C - F - Dm - G

The root notes in this example are: C, F, D, and G. When inverted, they become: G, D, F and C.

Transposed down a perfect fifth they become: C, G, Bb, and F.

Next we invert the chord types - major to minor, and vice versa. We end up with these negative chords:

Cm - Gm - Bb - Fm

Simple as that!

Negative Harmony: Practical Uses

Knowing how to figure out negative harmony is nice to talk about at the bar, but what are its practical uses?

You can use negative harmony to:

- Write new chord progressions related to the original key

- Start a new section, using previous thematic material

- Add flavor and interest at key points in the music

Let's look at the technique in action.

Full Positive Progression

We'll start with a basic chord progression (and yes, we're still in C major...):

C - Em - Am - F - C

Full Negative Progression

Next, we'll take the previous example and turn everything on it's head. The negative chord progression will be:

Cm - Ab - Eb - Gm - Cm

You can hear that the negative version sounds darker, but follows a similar harmonic shape as the original.

Nerd Alert!

If you're a music theory nerd you'll notice that the plagal cadence in the first chord progression has been replaced with an authentic cadence in this one.

Positive and Negative Progression

Negative harmony isn't an either/or option though. You're totally free to switch out positive chords for negative chords when it sounds good to you. Here, I'm replacing only the 2nd and 3rd chords with their negative cousins:

C - Ab - Eb - F - C

As with many things in music, less is often more, so don't feel obliged to use negative harmony for an entire chord progression.

Mixing it Up Some More

If you're feeling bold, you can even merge negative harmony with the positive world:

C + Cm

Em + Ab

Am + Eb

F + Gm

You need to be very careful with chord voicings if you attempt this, but it can lead to some interesting harmonic options.

In this next example, I've made the last chord (F) the 'blended' one (F with some flavors of Gm), before returning to the tonic chord.

How to Treat Extended Chords in Negative Harmony

So far we've only looked at primary triads, but how do you deal with major or minor 7th chords, added, 6ths, or other extended chords ?

If you're doing things the long way, simply invert any additional notes on top of the triad, remembering the rule that the root of the new chord will be a perfect fifth below the generator note.

For the shortcut way of figuring things out, remember how major chords invert to minor ones?

There's a similar principle for extended chords:

Minor 7th = major 6th

Major 7th = minor (b) 6th

Dominant (flattened) 7th chords = minor 6th

A C major 7th chord (C -E - G- B) will become a Cm(b)6 (C - Eb - G - Ab).

A G7 chord (G - B - D - F) will turn into Fm6 (F - Ab - C - D).

And so on!

Negative Scales

Negative harmony is great for all the things chord related. But if you're changing a harmony, chances are you will need to alter some melody notes.

You can simply switch out any dissonant notes for tones that match the new harmony.

But if you want to generate a new idea and turn a tune completely on its head, you'll need to dig a bit deeper.

The principle behind a negative scale is the same as for harmony; you flip the notes along an axis.

If we wanted to work out the negative scale for C Ionian mode (major scale), we'd take the notes:

C - D - E - F - G - A - B

Consult our conversion chart:

And we'd have our new scale of:

C - D - Eb - F - G - Ab - Bb

But it's not quite as simple as that.

Because you're inverting the notes of the melody, you'll also need to switch out the direction it travels from one note to the next.

So if your melody has an ascending perfect fourth (C to F) the negative version would become a descending perfect fourth (G to D).

As an abstract concept, this may be a little hard to grasp, but as you explore negative harmony further, things will begin to make sense. Trust me...

History of Negative Harmony

The idea of negative harmony as a theoretical concept was first introduced by Swiss composer Ernst Levy in his book A Theory of Harmony. He proposed that harmony could be seen as symmetrical, where intervals could be flipped around a central axis to create an inverted counterpart.

These ideas were lofty, academic musings at the time, but were later explored by jazz musician Steve Coleman.

In the twenty-teens, Jacob Collier introduced negative harmony to a broader audience. His infectious enthusiasm for the subject and clear explanations led many young musicians to embrace the technique.

What started as a niche topic has gone on to capture the imagination of young musicians, composers, and arrangers in wildly different genres, and is now used as a creative tool for reimagining traditional chord progressions and melodies.

Conclusion

A lot of folks think that negative harmony is a relatively new idea, but it's actually been around longer than the theory behind it.

Musicians and composers have been using negative notes and chords instinctively for a very long time, and it's especially common in genres like jazz, soul, and funk, where re-harmonizing chords is common.

In fact, most composers have probably been using it in their own music without realizing it.

The theory behind the concept is simply a way of explaining what’s happening and how to achieve it. It’s like learning to walk first, then later reading about how your legs work to make it possible.

So don't be scared of it!

Negative harmony, when used carefully, can bring new sounds and interesting textures to your own music or covers of popular songs.

So get creative, go forth, and exploreth negative harmony!